Beautiful Amulets and Blood Curses

Beautiful things have a price. They have a history, a bargain or contract – paid in blood – behind their beauty. The enamoring richness belies its hidden curse.

The golden amulet in the following scene of “Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl” embodies this idea:

At the start of this scene, Elizabeth beholds this forbidden amulet in the privacy of her bedroom until a knock intrudes upon her secret transgression. Frantically, she puts on her sleeping gown and conceals the bewitched trinket in between her breasts – hidden beneath her clothing and near the heart, as well as the center of her being. Then, the cursed beauty, or perhaps the affinity or desire for it, we cherish and hold literally near to our heart.

Why does she care for it? What in the amulet calls her to it? This unknown quantity hearkens to a prelapsarian part of our being; to the allure within Eve when she spied the tender fruit of knowledge, to the perverse curiousity that willed Pandora to unleash untold horrors into the world. It is the draw that women feel toward the unknown, and the undiscovered. A chance for something more, something new, something that speaks to the greater unknown part of her being. There is more to life for Elizabeth than the dull day-to-day pleasantries and errands designed to soothe the empty aristocratic mind of her father.

An ark, a grail, a briefcase that belongs to Marcellus Wallace. An evil trinket of unknowable value Elizabeth stores near her breast as her father, Weatherby, barges in to her bedroom. He comes in with his maidservants and a gift for her – a new dress, designed to restrict, and subdue: “women in London must have learned not to breathe”. She knowingly probes her father for the true reason for the gift; to look presentable as a wife for the newly promoted Commodore Norrington.

Weatherby’s amulet, what he covets, is his daughter. The beauty is clear to see, but the ugliness, the hidden curse, lies in the price society exacts upon him for her. And he willingly complies to the order to commidify her according to measures of youth and beauty. He plans to marry her to Norrington: to transfer her from his property to his property. The immorality being him choosing to (blood) sacrifice her – ala Iphigenia – to the altar of English society by trading her as property, rather than truly loving her as his daughter. That he treats her as an amulet is his evil, and it is one that he holds near to his heart.

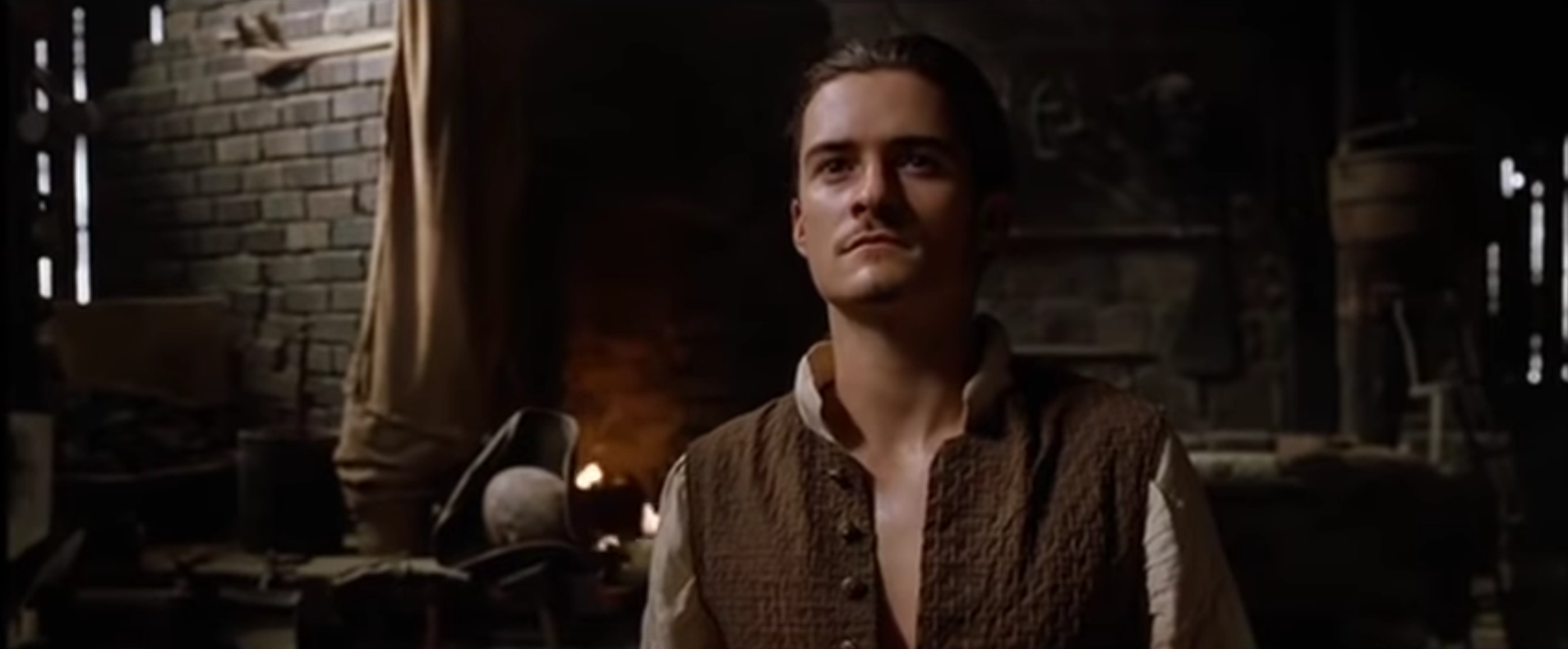

Will arrives with the sword Weatherby commissioned for Norrington. He stands off in the corner of the cavernous governer’s mansion. It is dimly lit, with furniture that’s drab, rather than grand. If anything, the decor looks old, rather than ornate. Yet Will – a rescued orphan that works as a blacksmith’s apprentice – waits near the corner of the room, unfamiliar and unused to the life of the aristocracy. He takes a fresh look around the room, perhaps with the most care of anyone in that house in recent memory. He inspects a candelabra fixed to the wall and, like any craftsman, grabs it out of curiousity.

It breaks, because the governor does not have anything of true value; playing in the game of the aristocracy causes him to sacrifice aesthetic sense and care for social standing and superficial appearance. Will deals with reliable tools and dangerous temperatures in order to forge deadly swords that soldiers entrust with their life during the heat of battle. Naturally, he wouldn’t expect a frail response from a presumedly metal fixture. Will’s life force is brimming with vitality, and so is anything he builds; frailty and degradation are as unfamiliar to him as are the tired, dilapidated customs and trappings of the British aristocracy.

But Will plays into the irony that somehow the governor’s worthless candelabra is valuable by hiding its brokeness: he stashes it into another neglected artifact, the umbrella holder. Perhaps what is valuable is hiding the fact that the governor doesn’t have anything of worth – preserving the illusion of the Emperor’s new clothes. Despite his talent and ability, Will respects – even admires – the rules and the absurdities of the social order he lives in: he not only serves his master, he outshines him yet takes none of the credit. He conducts himself with the appropriate dress and speech of the upper class. His amulet is his life in British society – it saved him from drowning, clothed and fed him, nurtured him into the young man he grew into. It provided the opportunity to achieve excellence, to fuel his ambition and industriousness. The beauty is the life he’s able to live, but the curse is his place in the social hierarchy. Will is doomed to always be in a lower place despite his high abilities and potential. The curse of the aristocracy is to drain him of his works, use, and unbridled vitality until he is old and decrepit. The system is a machine designed to grind him for all he’s worth.

And for his young counterpart and love interest, Elizabeth too has British society as her amulet. It has raised her into a beautiful woman who can attract any man. But the paradox and curse is that the choice is taken from her and given to her father by that society. These implicitly bound contracts place a spellbound tension when all three briefly meet in the lobby. The promising young man, beautiful young woman, and the politically-powerful older father all contend with each other, and with the greater unseen metaphorical forces of indomitable youth, unconquerable love, and the established, collective social will. Weatherby fearfully guides Elizabeth away from the powerful gravity of true love to her rightful place in British society. Will meanwhile appeals to her in the way he was taught to express himself – with proper British formality. Elizabeth, on the other hand, appeals earnestly to Will as an attempt to escape the pretense and manipulation of the proper British formality that has been nothing but a force to for her to contend with, navigate through, and ultimately run away from.

Through their spellbound state – held by forces, gifts, and curses outside themselves – they hopelessly continue on their predestined path. Will fails to break through the charade of social custom and Elizabeth follows her father to the carriage that will take her away to her new husband and new life. The symphony plays in the background as Will realizes the finality of the moment once he is left behind as the only one in the frame of an abandoned mansion. As with all men, he understands too late what he must do, and only after it has passed does he act with the guts and insight required of him merely seconds before: “Good day, Elizabeth”.

The soft sunlight warms Will’s face as he accepts the fact that he loves her, and that it is only hours before he loses her forever. The horns boom in the background, the hooves of fate and finality trample the foreground, and Elizabeth looks back once more at Will before she rides away from her childhood home – out of his sight and out of his life – forever. Wherein at the end of the scene we are left standing dumb and dumbfounded like Will, wondering whether earnest love can exist within the amulet of human society, and of what amulet we ourselves wear and by what beauty and curse we are unknowlingly spellbound by.